On Tactics: Leverage

Last time we ironed out the definition of “Tactics.” We cut our teeth on a solid foundation for applying combat power through Sun Tzu’s maxim to “pound the enemy flanks and fall on his rear.” Let’s build on that understanding by discussing a key aspect employed through indirect tactics: Leverage.

Barely used and never defined, leverage rarely appears in Army doctrine. One can find trite phrases like ‘leverage their experience,’ ‘leverage the enterprise,’ and ‘leverage external Service’ in FM 3-0 and FM 3-90, but all focus on gaining efficiency within or between internal and joint systems. This curious lack of mention in relation to tactics is baffling to me. Gaining or applying leverage has significantly impacted the tactical, operational, and strategic levels of war for centuries. Military history supplies endless examples, one of which we examine later. First, let’s analyze leverage a little further.

A lever is a simple machine that improves the ratio of force required to push, pull or lift an object. Leverage is produced by the action of a rigid bar of a given length fixed to a point (the fulcrum) and having force applied to a point separate from the fulcrum. If the distance is too short, one lacks mechanical advantage. Too long, and the machine will break.

Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary provides a superb definition as nouns and verbs.

Leverage: noun. 1: the action of a lever or the mechanical advantage gained by it

2: power, effectiveness

verb. 1. to provide or supplement with

2. to use for gain, exploit

Underlined are parts of the definition to highlight the impactful aspects of the application of combat power. These aspects make leverage a key component of tactics that enable the defeat of an enemy.

Now the Army has identified four commonly used defeat mechanisms: isolate, disintegrate (disrupt), dislocate, and destroy (FM 3-0, SEPT22). The tactical application of leverage enables these. Crucial to this is understanding the elements of tactical leverage: combat power, terrain, and initiative.

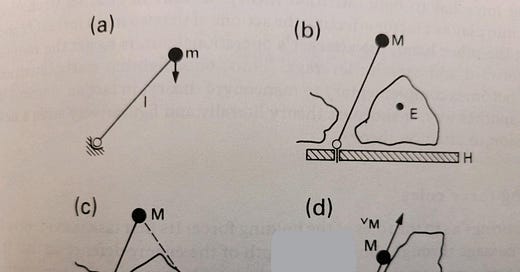

In Race to the Swift, Richard E. Simpkin expertly translates the components of a lever into the elements of combat power. Commonly understood in American doctrine as the “fixing force,” he calls the “holding force” (H). This provides the fulcrum. The lever arm he calls the “mobile force” (M) is known as the maneuver element in American doctrine. Finally, the object to be pulled, pushed, or lifted (as previously described) is the enemy (E).

No tactician can ignore the influence of terrain, especially concerning the creation of leverage. Which brings us back to the mantra: find the flanks! We can confidently presume the opposition will have two flanks, so analysis of terrain will determine which one (if not both) exposes them to attack or envelopment. This is the assailable flank (FM 3-90, July 2001).

One might regard the terrain associated with an assailable flank as decisive terrain. However, useable terrain lies within the tactician’s actual needs. Terrain will allow the maneuver element to achieve a position where leverage can be exerted. The depth of the maneuver element and the force applied to it determines the efficacy of leverage. In short, the longer the lever, the more force the enemy experiences. Combing the hinge effect between the fixing force and the maneuver element (the fulcrum and the lever arm) provides us tactical leverage.

Obviously, tactics are not conducted in a laboratory, free of variables that would taint the result. Fog, fear, friction, and fatigue provide ever-present factors all combatants wrestle with. Yet, these dynamics prove instrumental in the intangible element of leverage. The words of G.S. Patton best describe these intangible: “War is not about perfection, which is timeless, it is about opportunity which is chained to time.” (Patton, by Alan Axelrod)

The superior tactician recognizes that moment of opportunity and exploits it through initiative. The latitude to make tactical decisions within the commander’s intent is the power source of initiative. Derived from the Prussian/German term Auftragstaktik which translates into “mission-type orders” (better known in American doctrine as mission command), initiative is the critical element of applying leverage. These orders tell the tactician what to do. The exercise of disciplined initiative at the tactical level determines the how. Initiative is “the liberation of individual energies to ensure victory”1, and the ultimate goal in the use of leverage.

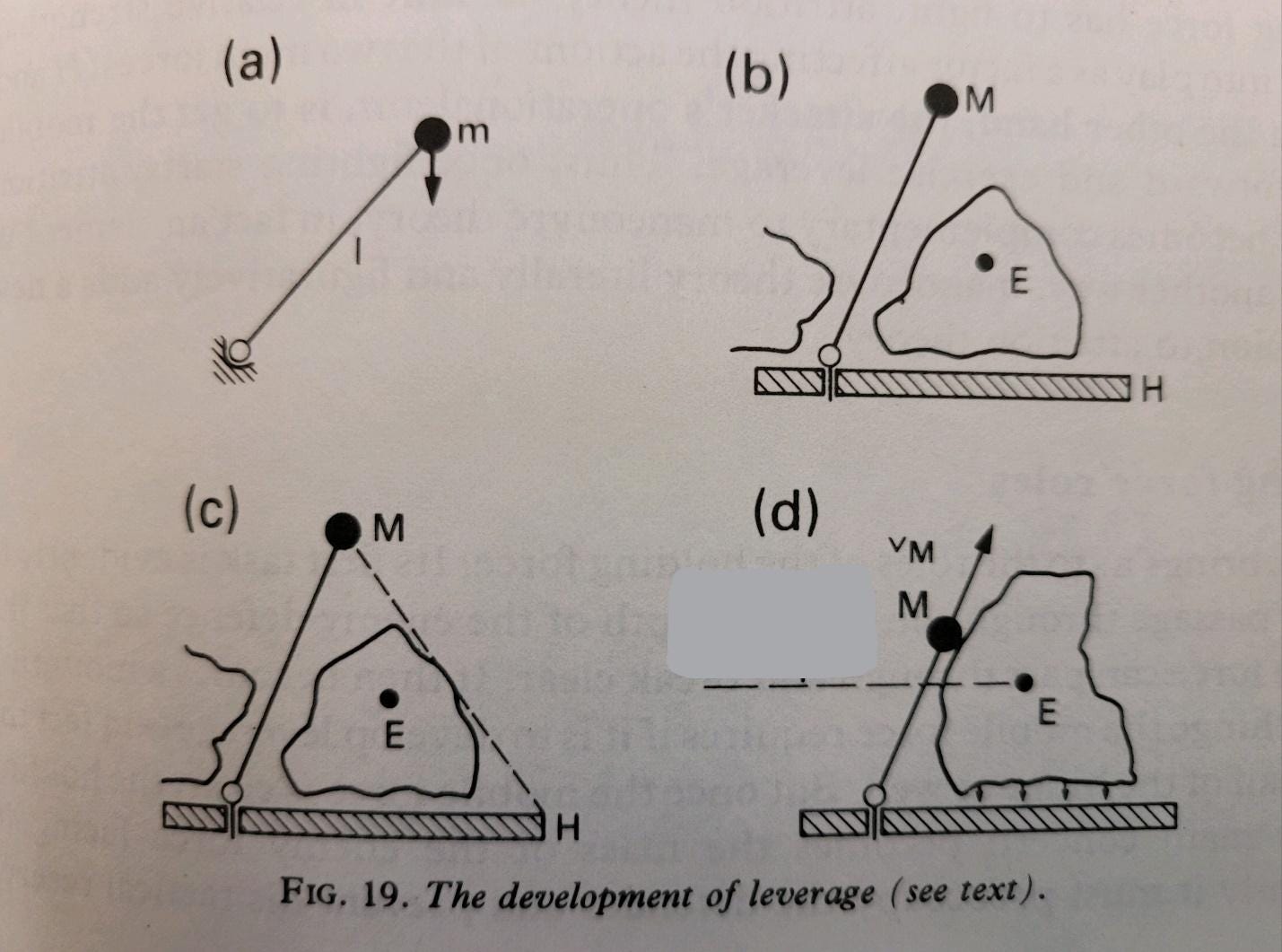

We can find all three elements of tactical leverage on display through the examination of The Battle of Prague, fought between the Prussians and Austrians in 1757. Regarding combat power, the Prussians and Austrians seemed relatively matched with a mix of infantry, cavalry, and artillery, numbering between 60-65,000 on each side. Terrain initially favored the Austrians, as they took up the nearly invincible position in the heights east of Prague. When the Prussians arrived, they immediately recognized the need to out-flank the heights with the goal of envelopment. The only assailable flank was on the eastern edge of the formation. The Austrians observed this maneuver and countered with the shift in forces to meet the threat. Friction prevented the Prussians from realizing a full envelopment. The maneuver element, slowed by a marsh littered with streams and ponds, did not reach far enough south to create the leverage needed to dislocate the Austrians. Yet, the Prussians continued to press the attack, resulting in the Austrians continuing to maneuver elements to meet them.

This presents a clear picture of the tangible pieces of tactical leverage: combat power and terrain. The Prussian main body (fixing force) holds Austrian’s assailable flank while the Prussian maneuver element turns out the Austria defense. Fulcrum, lever arm, and object. (see the graphic below)

1 Nicolson, A. (2005). Seize the fire: Heroism, duty, and the Battle of Trafalgar. Harper Perennial.

Red: Austrian defense. Solid Blue: Prussian fixing force. Dashed blue lines with blue arrows: Prussian maneuver element.

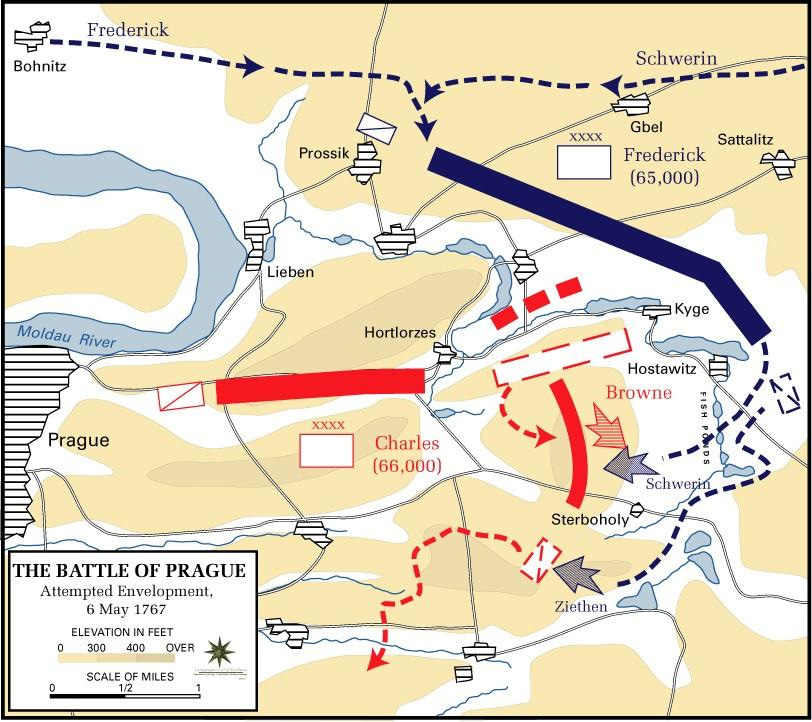

At this point, the battle rages and develops into a desperate affair. On both sides, casualty rates rise as they feed more units into the fray. The Austrians sensed victory when the Prussian cohesion in the south seemed to falter, so they pressed the attack, attempting to drive the Prussians back. This attack created a gap in the Austrian lines ripe for exploitation.

Now we can see the effects of that leverage pulling the Austrian position apart. While not the attempted envelopment's original intent or desired effect, Patton’s words, “opportunity is chained to time” proves true.

The Prussian commander-in-chief found, himself fully engaged in reorganizing to meet the Austrian assault in the south. The northern subordinate leaders observed and exploited the gap created in the Austrian lines. This resulted in a penetration. With Prussian units threatening the Austrian rear, Duke Charles withdrew, leaving the Prussian victorious on the battlefield.

Here stands a perfect example of the third aspect of leverage on display, the intangible aspect of initiative. The subordinate leaders recognized an opportunity, exercised disciplined initiative to exploit it, and arguably, their actions won the day for the Prussians.

Through this battle, we see leverage, the noun, in the advantage gained by the Prussians, and leverage, the verb, in the opportunity exploited. The Prussians provided a clinic through this battle that exercised and exemplified Sun Tzu’s maxim. Instead of trying to dislodge the Austrians by a direct assault on an elevated position, they steadily developed indirect tactics, they pounded the enemy flank with the attempted envelopment and ultimately fell on his rear by executing a penetration. The combination of combat power, terrain, and initiative created the leverage that disrupted and dislocated the Austrians, ensuring Prussian victory.

The basics of tactics are all here, so stick to the fundamentals and ultimately create the leverage to win.

Find the flanks!

Book of the Week

Stan McChrystal served for thirty-four years in the US Army, rising from a second lieutenant in the 82nd Airborne Division to a four-star general, in command of all American and coalition forces in Afghanistan. During those years he worked with countless leaders and pondered an ancient question: “What makes a leader great?” He came to realize that there is no simple answer

From the back:

“McChrystal profiles thirteen famous leaders from a wide range of eras and fields—from corporate CEOs to politicians and revolutionaries. He uses their stories to explore how leadership works in practice and to challenge the myths that complicate our thinking about this critical topic. With Plutarch’s Lives as his model, McChrystal looks at paired sets of leaders who followed unconventional paths to success. For instance. . .

Walt Disney and Coco Chanel built empires in very different ways. Both had public personas that sharply contrasted with how they lived in private.

Maximilien Robespierre helped shape the French Revolution in the eighteenth century; Abu Musab al-Zarqawi led the jihadist insurgency in Iraq in the twenty-first. We can draw surprising lessons from them about motivation and persuasion.

Both Boss Tweed in nineteenth-century New York and Margaret Thatcher in twentieth-century Britain followed unlikely roads to the top of powerful institutions.

Martin Luther and his future namesake Martin Luther King Jr., both local clergymen, emerged from modest backgrounds to lead world-changing movements.

Finally, McChrystal explores how his former hero, General Robert E. Lee, could seemingly do everything right in his military career and yet lead the Confederate Army to a devastating defeat in the service of an immoral cause.”

In Your Ears

The Hiring Board

These are the jobs that are currently open in Washington. Don’t let the opportunity pass you by! Visit this website for the most current openings.

Would You Like to Contribute?

Submit your article and pictures HERE